The Unicorn Hangover: A Decade of Reckoning Looms for Venture Capital

In the grand tradition of financial luminaries who possess crystal balls seemingly clouded by their optimism, Marc Andreessen, co-founder of Andreessen Horowitz, boldly proclaimed in June 2022, "I think we're going to see a pretty quick recovery. I think by the end of 2023, early 2024, we're going to be back to a much more normal environment." One can't help but be reminded of the dulcet tones of Charles Prince, then-CEO of Citigroup, who famously quipped in July 2007, just before the housing market imploded, "As long as the music is playing, you've got to get up and dance. We're still dancing." It seems the ability to tap dance around economic realities is a skill shared by titans of both traditional finance and the venture capital world. As we stand amid the rubble of tech layoffs and down rounds in early 2024, one might wonder if Andreessen and the Power Law Cartel are still dancing or if they've finally noticed that the DJ has long since packed up and gone home.

Behind the platitudes and posturing of the Power Law Cartel, the startup ecosystem and venture capital industry are entering an unprecedented era of disruption and realignment that will likely persist for the next decade, making it the single most extraordinary collapse in venture capital history. The current downturn is not a typical cyclical correction but a fundamental restructuring that will profoundly impact startup formation, growth, and funding well into the 2030s. The current crisis exhibits characteristics that suggest a far more protracted and challenging recovery period.

The Dot-Com Bust, on Steroids

To understand the gravity of the current situation, it's instructive to compare it with the dot-com era. During the dot-com bubble, the NASDAQ Composite index peaked at 5,048.62 on March 10, 2000, before losing 78% of its value by October 2002. In contrast, the current tech downturn has seen the NASDAQ fall by about 35% from its November 2021 peak to its lowest point in 2022.

The scale of the current crisis is vividly illustrated by the wave of layoffs sweeping through the tech industry. Over 260,000 tech employees were laid off in 2023, with the trend continuing into 2024. This surpasses the estimated 100,000 layoffs in the San Francisco Bay Area alone during the dot-com bust. The breadth of these layoffs, affecting even tech giants like Meta (11,000 jobs cut) and Amazon (18,000 jobs cut), indicates a fundamental reset of growth expectations in the tech sector.

The funding landscape presents an equally stark picture. Q1 2024 data reveals that the proportion of flat and down rounds reached 27.4%, the highest level in a decade. During the dot-com crash, down rounds peaked at about 30% in 2002. However, the recovery was relatively swift, with down rounds decreasing to about 20% by 2003. The persistence of high rates of down rounds four years into the current downturn suggests a more fundamental and prolonged repricing of the startup ecosystem.

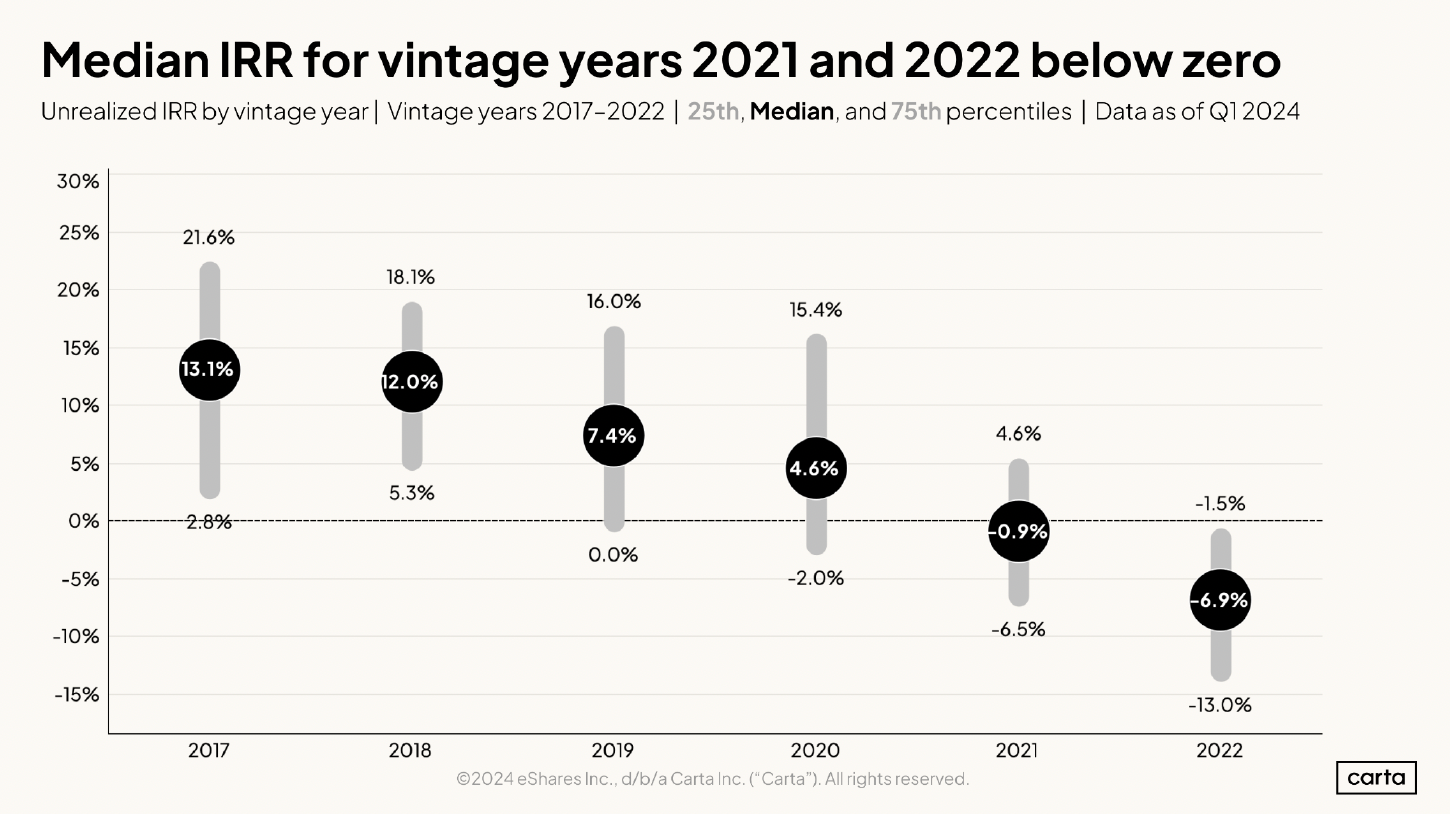

Moreover, fund performance data provides compelling evidence of a protracted liquidity crisis. Less than 10% of 2021 vintage funds have provided any distributions to paid-in capital (DPI) after three years. This starkly contrasts to the dot-com recovery, where by 2003 (three years after the crash), many VCs had begun returning capital to LPs, albeit at lower levels than during the boom years.

The slowing progression of startups through funding stages further underscores the depth of the current crisis. Only 15.4% of Q1 2022 seed startups progressed to Series A within two years, compared to 30.6% for the Q1 2018 cohort. While comparable data from the dot-com era is limited, research from the National Venture Capital Association shows that by 2004, four years after the crash, startup formation and progression rates had begun to recover.

Secondary Markets are the Canary in the Coal Mine

Amidst the broader downturn in the venture capital ecosystem, the secondary market for private company shares has emerged as a thriving arena, painting a telling picture of the industry's desperation. According to data from Forge Global, secondary transaction volumes hit record highs in 2023, with over $10 billion in shares changing hands. This surge in activity is not a sign of health but rather evidence of VCs and other investors frantically offloading overpriced assets.

In the wake of the dot-com bubble burst, secondary markets for private company shares were virtually non-existent. The concept of organized, liquid markets for private stock was in its infancy, with platforms like SecondMarket and SharesPost only emerging in the late 2000s. Instead, the dot-com era was characterized by a wave of outright failures, with many startups simply ceasing operations and leaving investors with worthless paper.

According to a study by the National Venture Capital Association, nearly 40% of venture-backed companies founded between 1997 and 2000 had failed by 2002. In contrast, the current downturn has seen relatively fewer outright failures but a surge in secondary market activity. Forge Global reports that transaction volumes on their platform increased by 87% year-over-year in 2023, reaching $3.2 billion in Q4 alone.

This difference is crucial. During the dot-com crash, the rapid failure of overvalued companies allowed for a quicker market reset. Bad investments were written off, and capital could be reallocated to new ventures relatively quickly. The recovery, while painful, was swift – by 2003, VC investment had begun to rebound, and new startups like Facebook were already being founded.

In contrast, the current robust secondary market acts as a pressure release valve, allowing overvalued assets to be sold at a discount rather than failing outright. While this might seem preferable on the surface, it could actually prolong the downturn. The Zanbato ZX index shows an average discount of 38% to the last primary funding round, but this gradual repricing could take years to fully play out.

Furthermore, the secondary market's growth has introduced new dynamics that were absent in the dot-com era. For instance, data from Industry Ventures suggests that over 60% of secondary purchases in 2023 were made by crossover funds and other non-traditional venture investors. This influx of new buyers could artificially prop up company prices instead of letting them fail, delaying the necessary market correction.

The existence of a liquid secondary market also changes the calculus for VCs and founders. Instead of being forced to seek an exit through an IPO or acquisition, stakeholders can now obtain partial liquidity through secondary sales. This could lead to companies staying private longer, further extending the timeline for overall market recovery.

While the dot-com crash was a sharp, painful reset that cleared the way for new growth, the current downturn, fueled by an active secondary market, may result in a longer, more drawn-out period of value destruction and repricing. The thriving secondary market, far from being a silver lining, may well be the canary in the coal mine, signaling a protracted period of value destruction and diminished opportunities in the startup ecosystem.

The exit landscape for startups has also fundamentally shifted. Exit step-ups are at historic lows, with the median VC step-up at exit for acquisitions dropping to approximately 1.2x in 2024. The IPO market remains largely closed, with only a few venture-backed IPOs in recent quarters. This contrasts sharply with the dot-com recovery: while IPOs dropped from 264 in 1999 to just 22 in 2001, by 2004, the market had rebounded with 93 venture-backed IPOs.

The Fundamentals Don't Add Up to a Quick Recovery

Several underlying fundamentals that led to the recovery from the dot-com crash are notably absent or different in the current environment:

Interest Rates: Post-dot-com, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates aggressively, dropping from 6.5% in 2000 to 1% by 2003. This cheap capital fueled the recovery. In contrast, we're currently in a high interest rate environment, with the federal funds rate at 5.25%-5.50% as of 2023 and likely to remain elevated for an extended period.

Technological Advancements: The years following the dot-com crash saw significant technological advancements, including the proliferation of broadband internet and the rise of social media, which created new opportunities for startups. While AI presents similar potential today, it is still very early on the innovation curve, and its impact is still being determined and may take longer to materialize fully.

Global Competition: The dot-com era was primarily a U.S. phenomenon. Today, the U.S. faces significant competition from other global tech hubs, particularly in China and Europe, potentially slowing its ability to reassert dominance quickly.

Market Saturation: Much of the low-hanging fruit in consumer internet services, which drove the recovery from the dot-com crash, have already been picked. Today's opportunities often require more capital and longer development cycles and face more entrenched incumbents.

Regulatory Environment: The regulatory landscape for tech companies is far more complex and stringent today than it was post-2000, potentially slowing innovation and growth in certain sectors.

The convergence of these factors – widespread layoffs, increasing down rounds, slowing startup progression, a challenging exit environment, and less favorable macroeconomic conditions – all point to a recovery period that could extend well into the 2030s. This "nuclear winter" represents not just a downturn but a fundamental restructuring of the startup economy and venture capital industry.

What to Expect in the Future

As we navigate this extended period of change, we can expect to see several key developments:

- A shift towards more sustainable, revenue-focused business models in startups, moving away from the growth-at-all-costs mentality of the past decade.

- A consolidation in the VC industry, with many smaller firms struggling to raise new funds and larger firms becoming more conservative in their investment strategies.

- The emergence of new funding models and structures designed to better align investor and founder interests in a more challenging market environment.

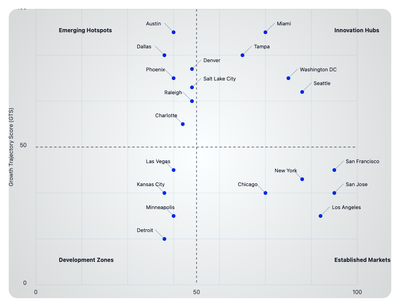

- A potential geographic redistribution of startup activity, as high costs in traditional tech hubs become unsustainable for cash-strapped startups.

- An increased focus on deep tech and hard science innovations that offer more defensible market positions, as opposed to the quick-scaling software startups that dominated the past decade.

Light the Torches and and Sharpen the Pitchforks

The startup economy and venture capital industry are not merely weathering a storm; they are navigating through a fundamental paradigm shift that will reshape the landscape for years to come. The depth and breadth of this disruption call for more than just passive adaptation or waiting out the winter. It's time for every venture capital value chain participant - from founders and employees to investors, limited partners, and even policymakers - to grab their proverbial torches and pitchforks and march toward radical reform.

Founders must reimagine their growth strategies, prioritizing sustainable business models over the illusion of hypergrowth. Employees must arm themselves with diverse skill sets and realistic expectations about equity compensation. Investors should overhaul their evaluation metrics and portfolio management practices, moving away from the "unicorn or bust" mentality. Limited partners must demand greater transparency and align their return expectations with the new reality of extended holding periods and slower growth trajectories.

Moreover, policymakers and industry leaders need to collaborate to create a more resilient and inclusive innovation ecosystem. This could involve rethinking regulations around startup funding, IPOs, and secondary markets, as well as initiatives to democratize access to venture capital across geographies and demographics.

The clarion call is clear: the old playbook is obsolete, and incremental changes won't suffice. It's time to storm the bastions of outdated venture capital practices, question every assumption, and forge a new path forward. This is not just about surviving a downturn; it's about reimagining and rebuilding a more sustainable, equitable, and innovative startup economy for the decades to come. The torches are lit, the pitchforks are sharpened—now, who will lead the charge?

References

- Carta. (2024). VC Fund Performance Report Q1 2024. Carta Inc.

- PitchBook & National Venture Capital Association. (2024). Venture Monitor Q1 2024. PitchBook Data, Inc.

- Layoffs.fyi. (2024). 2023-2024 Tech Layoff Tracker. Retrieved from https://layoffs.fyi/

- NASDAQ. (2022). NASDAQ Composite Index Historical Data. NASDAQ, Inc.

- Federal Reserve. (2023). Federal Funds Effective Rate. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US).

- National Venture Capital Association. (2005). The Venture Capital Industry: An Overview. NVCA.

- Ritter, J. R. (2022). Initial Public Offerings: Updated Statistics. University of Florida.

- Gornall, W., & Strebulaev, I. A. (2020). The Economic Impact of Venture Capital: Evidence from Public Companies. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(4), 1508-1556.

- Kauffman Foundation. (2012). We Have Met the Enemy... And He is Us: Lessons from Twenty Years of the Kauffman Foundation's Investments in Venture Capital Funds and the Triumph of Hope Over Experience. Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.

- CB Insights. (2024). The State of Venture Q1 2024. CB Insights.

- Preqin. (2024). Venture Capital Deals and Exits Q1 2024. Preqin Ltd.

- Silicon Valley Bank. (2024). State of the Markets Report Q1 2024. SVB Financial Group.

- Y Combinator. (2023). YC Startup Index 2023. Y Combinator.

- Deloitte. (2024). 2024 Technology Industry Outlook. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited.

- Cambridge Associates. (2024). U.S. Venture Capital Index and Selected Benchmark Statistics. Cambridge Associates LLC.

- Dow Jones VentureSource. (2005). Venture Capital Industry Report 2000-2005. Dow Jones & Company.

- Lerner, J., & Nanda, R. (2020). Venture Capital's Role in Financing Innovation: What We Know and How Much We Still Need to Learn. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(3), 237-61.

- Gompers, P., Kovner, A., Lerner, J., & Scharfstein, D. (2008). Venture capital investment cycles: The impact of public markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 87(1), 1-23.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2024). Employment Situation Summary. United States Department of Labor.

- PwC/CB Insights. (2024). MoneyTree Report Q1 2024. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP.

No spam, no sharing to third party. Only you and me.

Member discussion