Venture Reciprocity

Noam Wasserman famously shed light on founder longevity in his research, which he published in Harvard Business Review (HBR) 5 years ago. “By the time the ventures were three years old, 50% of founders were no longer the CEO,” Wasserman observed. “In year four, only 40% were still in the corner office and fewer than 25% led their companies’ initial public offerings.”

It would be logical to assume these decisions are made as result of poor performance. But chronicling founder experiences, including my own, reveals founders are often forced out during certain peaks in overall performance and results.

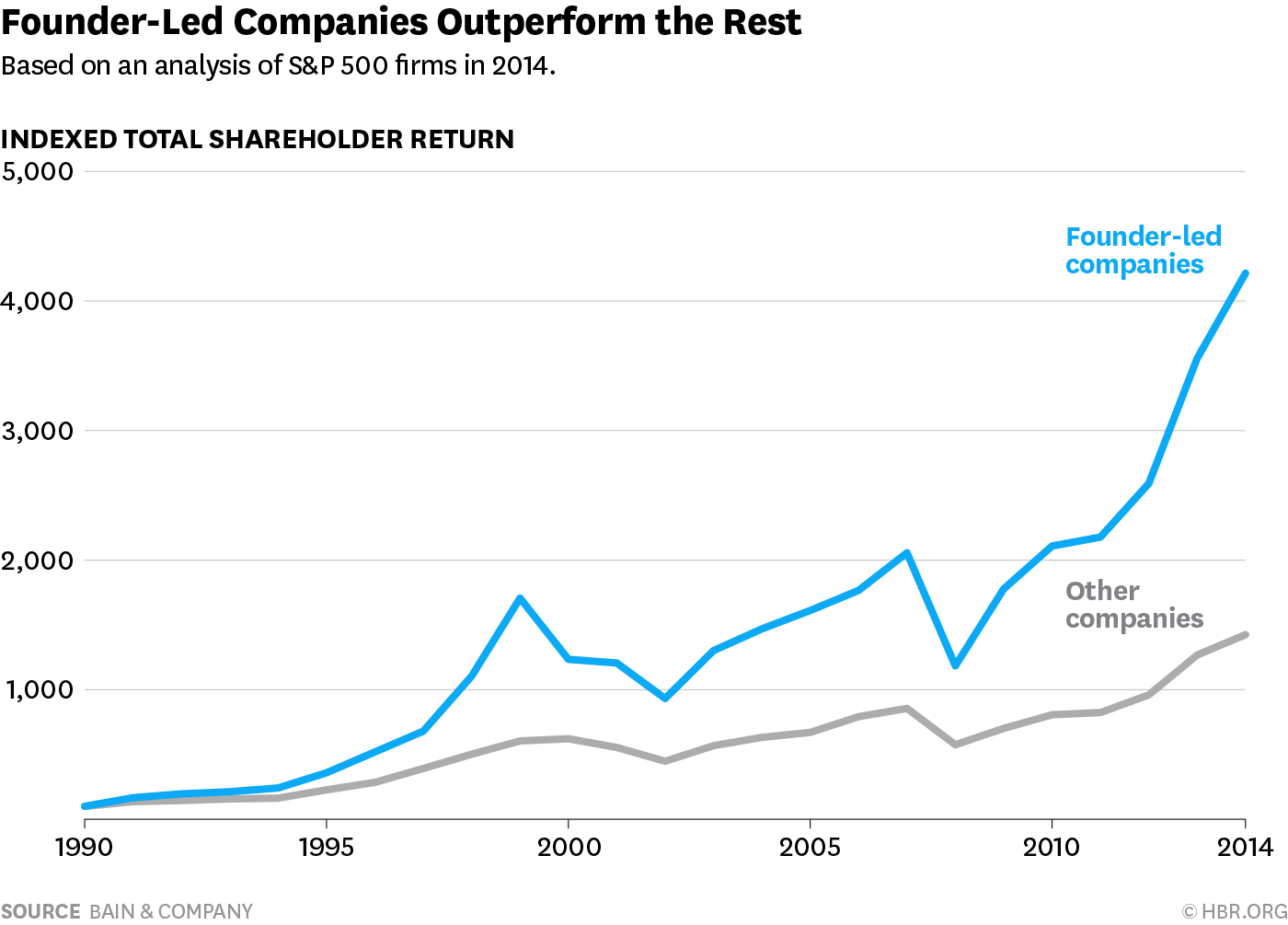

These facts seem odd, if not entirely irrational, when you consider the that founder-led companies on the S&P wildly outperform non-founder led companies, as research by Chris Zook illustrated in his 2014 HBR article. I call this the Founder Investor Paradox.

The following analysis attempts to deconstruct the Founder Investor Paradox to explain the why Boards get rid of company founders. Finally, we will explore a path toward a more healthy and productive partnership between founders, the investors that support them and the Board of Directors that have a fiduciary responsibility to shareholders.

The Venture Capital Ethos

Often hiding in plain sight, camouflaged by a dress-down work attire and inviting quips such as “I just want to be helpful”, the Venture Capital Ethos is a mutation of capitalism born of the contemporary unicorn venture investment thesis. There are five tell-tale signs of the Venture Capital Ethos:

- Survival Instinct: Investors have an inherent survival instinct. This instinct drives them to acquire resources and accumulate wealth as a means of ensuring their survival and well-being. Greed is a natural manifestation of this instinct, where investors routinely demonstrate an insatiable desire for more than what is necessary for survival.

- Scarcity Mindset: The perception of limited resources can fuel a sense of scarcity, leading to a fear of missing out or being deprived. In such situations, investors become more inclined to pursue excessive equity ownership to safeguard against potential scarcity, often ignoring the consequences to others, such as customers, employees and founders.

- Social Comparison and Status: Investors often engage in social comparisons. Greed can emerge from the desire to achieve or maintain a higher social status relative to others. We see this actively playing out in markets like Silicon Valley, where venture investing practitioners are held in high esteem.

- Reinforcement and Rewards: Venture capitalists place a high value on material wealth accumulation because they are rewarded for it with support for more lucrative investment funds. This positive reinforcement for acquiring more can encourage greedy behavior, as investors seek the rewards and recognition that come with it.

- Cognitive Biases: Various cognitive biases, such as loss aversion and the endowment effect, can influence human behavior and also contribute to greed. Loss aversion refers to the tendency to place more value on avoiding losses than acquiring gains, which can lead investors to be overly protective of their equity position and cause a need to accumulate more. The endowment effect causes investors to overvalue their role and purpose in a startup, making them reluctant to consider any decision or course of action that doesn’t further enrich their position.

I contend the Venture Capital Ethos is a product of the contemporary “Unicorn Investment Thesis” that has all but taken over the VC asset class.

The Unicorn Investment Thesis refers to the idea that venture capitalists should invest in startups that have the potential to achieve a $1 billion valuation or more. This thesis has led to an over-emphasis on investing only in companies that have the potential for rapid growth and high returns.

The size of modern venture capital conflicts with both the capital needs and return distributions of early-stage companies. There will never be enough "unicorns" requiring sufficient capital to support the investment strategy of the “unicorn hunter” VC.

Thus, VCs tend to make adversaries out of the startup founders, which is both illogical an unnatural considering both should adhere to the same goals and objectives.

The Board of Directors Groupthink Outgrowth

Board of Directors groupthink, the ultimate cause of irrational governance decisions, is a cancerous tumor catalyzed by the Venture Capital Ethos. In other words, the Venture Capital Ethos creates the perfect environment for groupthink to thrive.

Groupthink occurs when a group of people prioritize consensus and harmony over critical thinking and independent decision-making. In the context of startup boards and investors, groupthink leads to irrational and dysfunctional decision-making outcomes.

Documenting founder experiences reveals a set of consistent and observable themes that often precipitate catastrophe:

Illusion of Invulnerability: Board members develop a sense of overconfidence, leading them to take excessive risks or overlook potential pitfalls in their decisions.

Collective Rationalization: The board may ignore warnings and negative feedback, justifying their decisions despite clear evidence of their potential flaws.

Belief in Inherent Morality: Members may believe in the moral rightness of their group and its decisions, which can blind them to ethical or legal considerations.

Stereotyping of Out-Groups: Boards may dismiss the opinions of outsiders or those who disagree with them, viewing them as adversaries or less knowledgeable.

Direct Pressure on Dissenters: There can be direct pressure on members who express doubts or different opinions, pushing them to conform to the majority view.

Self-Censorship: Members who have doubts or differing opinions might keep silent to avoid rocking the boat, leading to a lack of voiced dissent.

Illusion of Unanimity: The silence of dissenters is often interpreted as agreement, creating a false sense of consensus.

Mindguards: Some members might take on the role of protecting the group from dissenting opinions or negative information, further insulating the group from reality.

Members of the board, driven by a desire to maintain unity and avert risks, develop an illusion of invulnerability and engage in collective rationalization. They dismiss dissenting opinions, stereotype out-groups, and exert direct pressure on dissenters to conform to the majority view.

This collective mindset eventually obstructs critical analysis, limits the exploration of alternatives, and hampers effective planning and preparation often with spectacular consequences (see 2023 OpenAI drama as an example).

Ethical considerations and moral obligations can be easily overlooked in the pursuit of the perceived "greater good." The consequences of groupthink are catastrophic to startup founders, as decisions may be made without adequate risk assessment and consideration of long-term implications. It is in this state of complete dysfunction that the Founder - Investor Paradox plays out.

The Law of Venture Reciprocity

Appealing to investors natural propensity for risk management is the antidote to the destructive actions that stem from the potential for negative consequences of the Venture Capital Ethos.

Humans have a natural inclination towards reciprocity, which is the desire to return favors and repay kindness. When someone provides us with support, resources, or assistance, we feel an internal obligation to reciprocate their generosity. This sense of indebtedness fosters a psychological bond that discourages harmful actions towards the provider.

The same is true in the relationship between founders and investors, which I call the law of Venture Reciprocity. In the context of the venture capital investor, we mistakenly assume that “equity” is the basis of reciprocity.

Placing equity at the center of Venture Reciprocity means investors will expect a large multiple as a return on their investment. Specifically, they expect that the company will be monetized at a high-enough price that their investment will return at least ten times their investment. For example, if I raise $1M in “equity” financing, the investor is going to price the deal based on a 10x return expectation. The price of that capital to the founder is a whopping $10M. Investors actions and behavior will be solely focused on getting this $10M - even if it means selling the company for $11M after recapitalizing and soaking up all the equity from everyone else.

A lack of predictability in equity returns forces the investor to price the risk of investment absurdly high, which comes directly out of the pocket of the company’s founders. More specifically, the problem with “equity” as the basis of creating Venture Reciprocity is the inherent lack of returns predictability across two vectors, namely Value and Time. How much is returned to investors and how long it takes to create that return is the crux of the problem.

In truth, “returns” are the better proxy. The presence of returns is inversely correlated to consequential actions borne of the Venture Capital Ethos - forced liquidations, premature exits, recapitalization schemes, etc. in pursuit of yield from the Unicorn Investment Thesis. In other words, the greater the probability of returns made to investors more quickly, the less likely a founder will experience the full brunt of the Venture Capital Ethos.

Programming Venture Reciprocity

Programming returns as the basis of Venture Reciprocity could be accomplished using universal KPI metrics like revenue. What if early stage investors, who often take the greatest risks, were to receive nearer-term returns calibrated to the amount of the risk actually taken?

The relationship between founders and investors is a crucial element that can either make or break the success of startup innovation.

Moving forward, innovating risk management can play a crucial role in designing terms and conditions that acknowledge and account for the Venture Capital Ethos. Preventing future founder injustices without jeopardizing the important role of early-stage speculative capital investment comes down to turning the same knobs and dials that investors use to create unfair advantages, rather than trying to legally paper around the risks.